A few weeks ago, Dr. Jamila Perritt and I represented Washington Area Women’s Foundation’s DC Family Planning Project (DCFPP) on a panel at the annual Society of Family Planning (SFP) Conference. The panel was about prioritizing equity and community engagement in contraceptive access work. We told attendees that the progress of the DC initiative so far is as much about what we have decided not to do as it is about what we have decided to do here in DC.

Let me explain! Our DC initiative is among a growing number of contraceptive access projects nationwide that have decided not to center our work or define our success based on increasing uptake of long-acting reversible contraceptives (methods of birth control that provide effective contraception for an extended period without requiring user action — including injections, intrauterine devices (IUDs) and subdermal contraceptive implants). Instead, we are trying to learn more about what DC residents want and need with respect to their reproductive health and then to define success around how we can contribute to adapting health care service delivery to meet those needs.

To provide some background regarding where the DCFPP started and where we are now …. the idea for a DC contraceptive access project came from an initiative in Colorado that was designed to improve access to LARCs. The Colorado project provided training, operational support, and low- or no-cost LARCs to low-income women statewide. Colorado reported significant increases in LARC uptake and reductions in unintended pregnancy and abortion. Many states followed suit with similar initiatives — focusing on LARCs, targeting low-income women, and measuring success by increases in LARC uptake and decreases in unintended pregnancy.

When a similar project was discussed in DC, concerns were raised about a “one size fits all” approach to contraceptive access. So, The Women’s Foundation, in partnership with a coalition of local funders and providers, commissioned a DC Family Planning Community Needs Assessment, which was conducted by the GW Milken Institute School of Public Health.

Through the needs assessment, we learned that reproductive health services and contraceptive methods (including LARC methods) actually already are widely available in DC; however, there is a disconnect between the availability/accessibility of these services and the utilization of them. We also learned that a significant number of sexually active adolescents and young women in DC are not accessing health care services at all. Additionally, the results showed low knowledge levels, negative perceptions, suspicions, mistrust and safety concerns about birth control methods (especially LARC methods) – particularly among young women of color from low-income households.

Given the study results, we realized that we needed to assess, understand and mitigate potential unintended harm to our community if we initiated a LARC-focused project directed at low-income households, which predominately include people of color in DC. It became clear that there are many issues other than the ability to access highly effective birth control methods or a desire to reduce unintended pregnancy that are impacting contraceptive and reproductive health care decision making in our community.

There is a long history of reproductive coercion and abuse against African Americans in the U.S., including nonconsensual medical experiments, compulsory sterilization, the Tuskegee Untreated Syphilis Study, and — more recently, unconstitutional, coercive laws proposed to incentivize or require welfare recipients to use the contraceptive implant, Norplant; disproportionate marketing to Black women of the injectable contraceptive Depo-Provera; and judges offering inmates reduced sentences if they agree to be sterilized or use contraception.

As a result of the DC needs assessment findings, our reproductive health/racial equity research, and recognition of how historical injustices and resulting mistrust may affect reproductive health care decision making, we believe that:

- method-effectiveness is not necessarily the main priority in all patient’s decision-making regarding contraception;

- some patients do not want LARC methods for a variety of reasons;

- access barriers are not necessarily as simple as method availability and having enough clinicians trained to provide them; and

- unintended pregnancy is not universally viewed as a problem that needs to be prevented.

We also believe that the community the DC initiative is intended to serve should guide the identification of the problem(s) to be addressed, as well as the potential solutions that best fit the needs of the community. Thus, we are focusing on whether people are able to access the services they need and want, and whether they experience those services positively, and ultimately whether their reproductive quality of life improves.

Admittedly, these outcomes are harder to quantify and thus, more difficult to fund. Yet, we believe this is the right approach for our community.

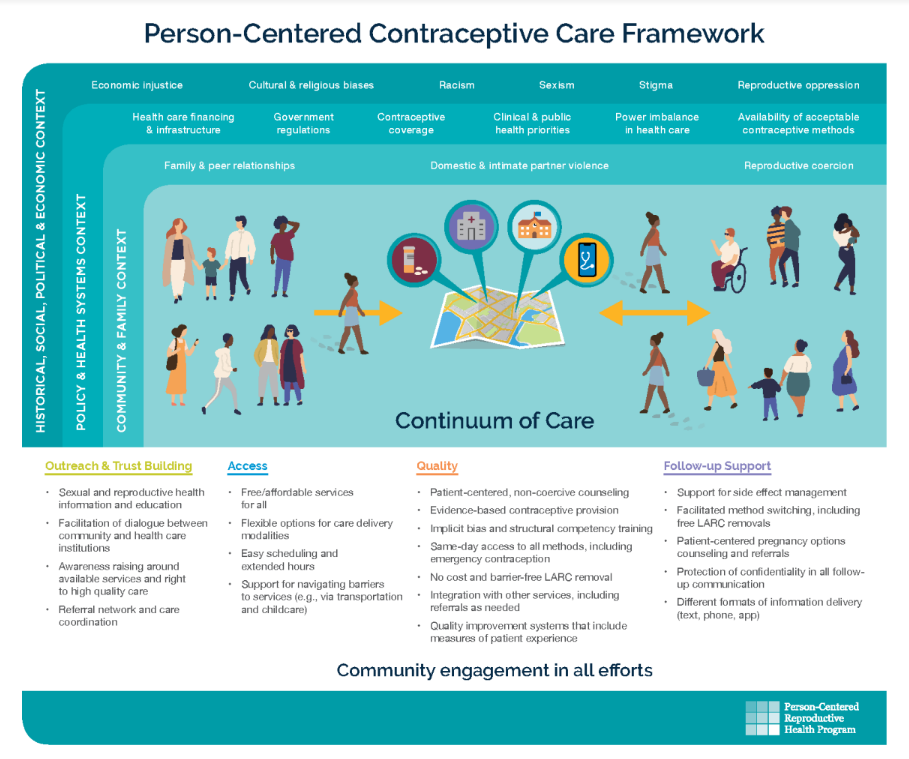

We currently are partnering with like-minded contraceptive access initiatives from Mississippi, Chicago, Boston and Utah, in collaboration with the UCSF Person Centered Reproductive Health Program, to form a national collaborative to develop shared evaluation measures for our contraceptive access work that do not focus solely on LARC devices and unintended pregnancy prevention. We hope to jointly develop shared language; to strengthen our messaging to funders regarding the value of investing in equity/justice/quality-focused contraceptive access initiatives that go beyond LARC access to tackle wider quality issues; and to better identify and articulate how we can define success with this work.

Circling back to a key takeaway from the SFP Conference, in order to move toward more equitable reproductive health care for all people, more philanthropic organizations must be willing to invest in people-centered contraceptive access initiatives that are built from the bottom up rather than the top down. These endeavors require “thinking outside the box” and a willingness to fund projects that are lifted up by the communities meant to be served to solve problems identified by the communities meant to be served through promising interventions conceived and designed by the communities meant to be served. In order to live our values regarding racial equity in reproductive health, we must be willing to change the systems and practices that hold racial inequities in place.